⚠️ Financial Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial, investment, or trading advice. All data and analysis reflect opinions current as of publication and may change without notice. Always conduct your own research or consult with a licensed financial advisor before making investment decisions. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Compounding is often celebrated as one of the most powerful forces in finance. Investors learn early that money left to grow over decades can multiply into extraordinary sums. What is rarely emphasized, however, is how quietly inflation reduces that growth. While compounding builds wealth through time, inflation erodes its purchasing power at the same pace, often unseen until decades have passed.

This creates a paradox. The longer you invest, the more compounding works in your favor, but the longer inflation persists, the more of your real return it consumes. Investors who track their portfolios in nominal terms may feel wealthier each year, yet find that what their money can actually buy has grown far less.

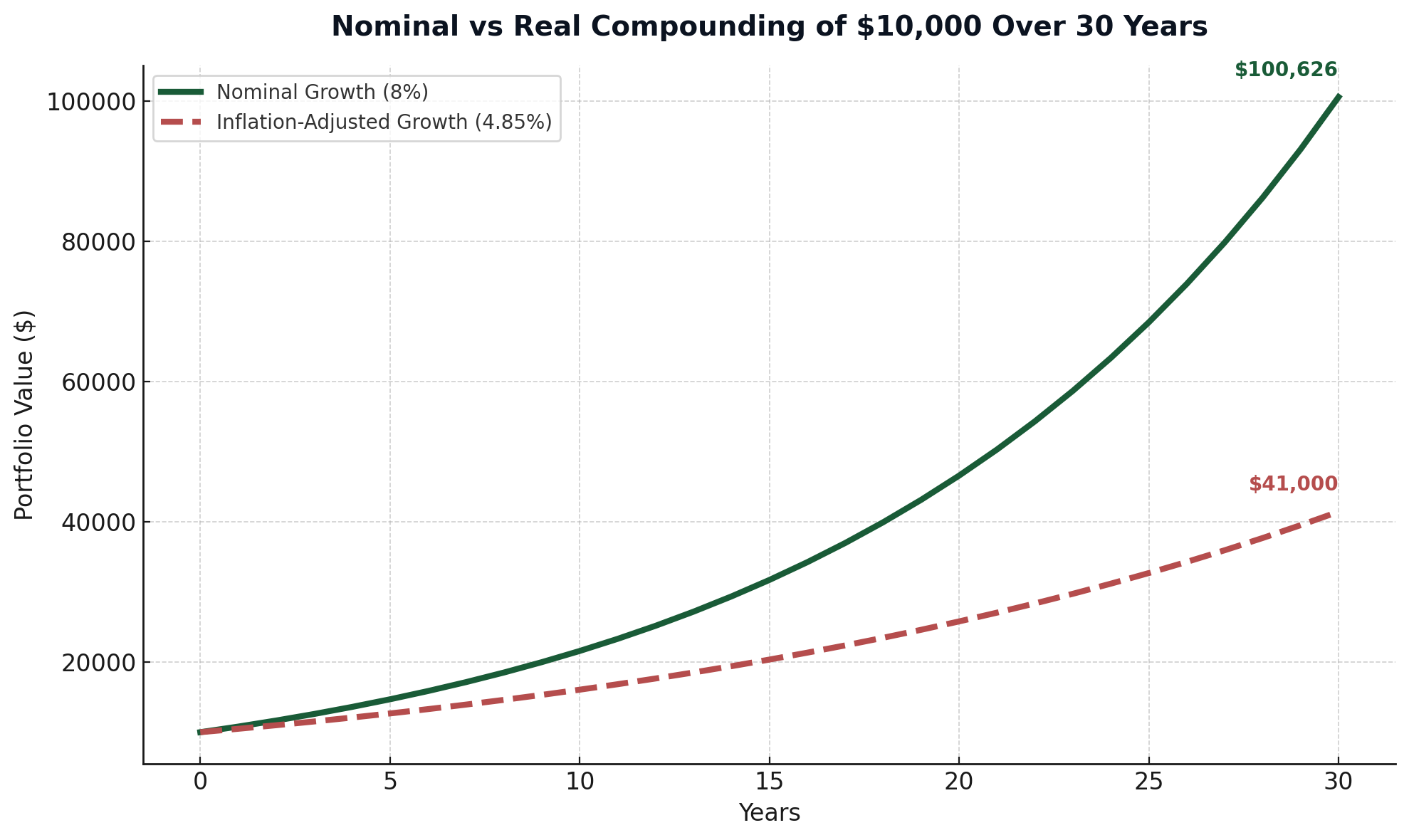

Consider this: an 8 percent annual return appears impressive on paper, but if inflation averages 3 percent, the true rate of growth in purchasing power is closer to 5 percent. Over one year, the difference is small. Over thirty years, the gap becomes enormous. Ten thousand dollars compounding at 8 percent grows to more than one hundred thousand. At 5 percent real growth, it reaches only forty-three thousand in today’s dollars.

Inflation acts as a silent tax on time. It does not take money from your account, but it diminishes what that money can do. Understanding this relationship is not optional for long-term investors; it is the difference between preserving wealth and simply watching numbers grow.

💡 TL;DR — How Inflation Impacts the True Power of Compounding Over Decades

- Inflation quietly reduces the real value of compounding by lowering purchasing power over time, even as nominal returns appear strong.

- An 8% nominal return with 3% inflation produces a 4.85% real return, cutting long-term purchasing power by nearly 60% over 30 years.

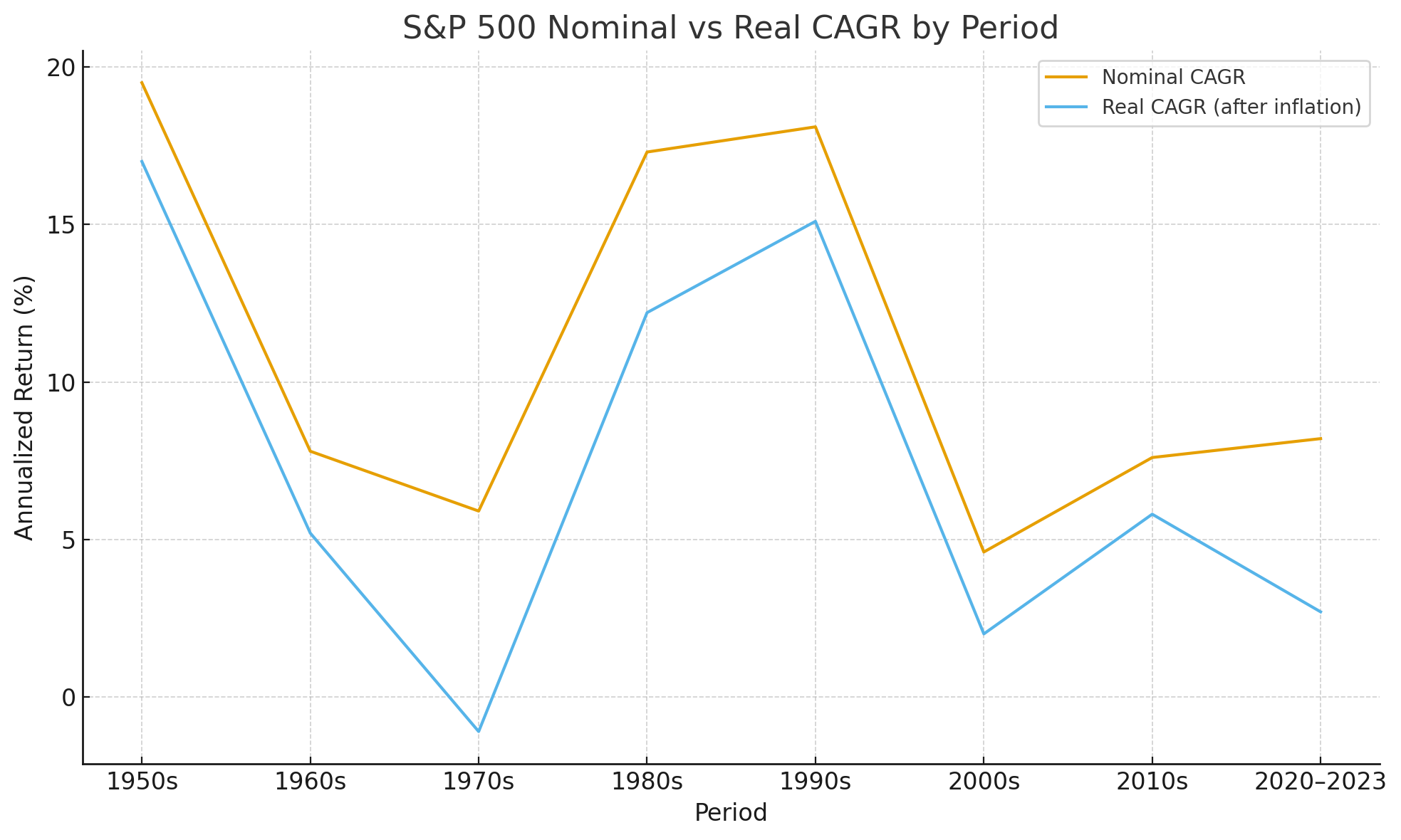

- During high-inflation decades such as the 1970s and 2020s, real S&P 500 returns dropped below 3% despite strong nominal growth.

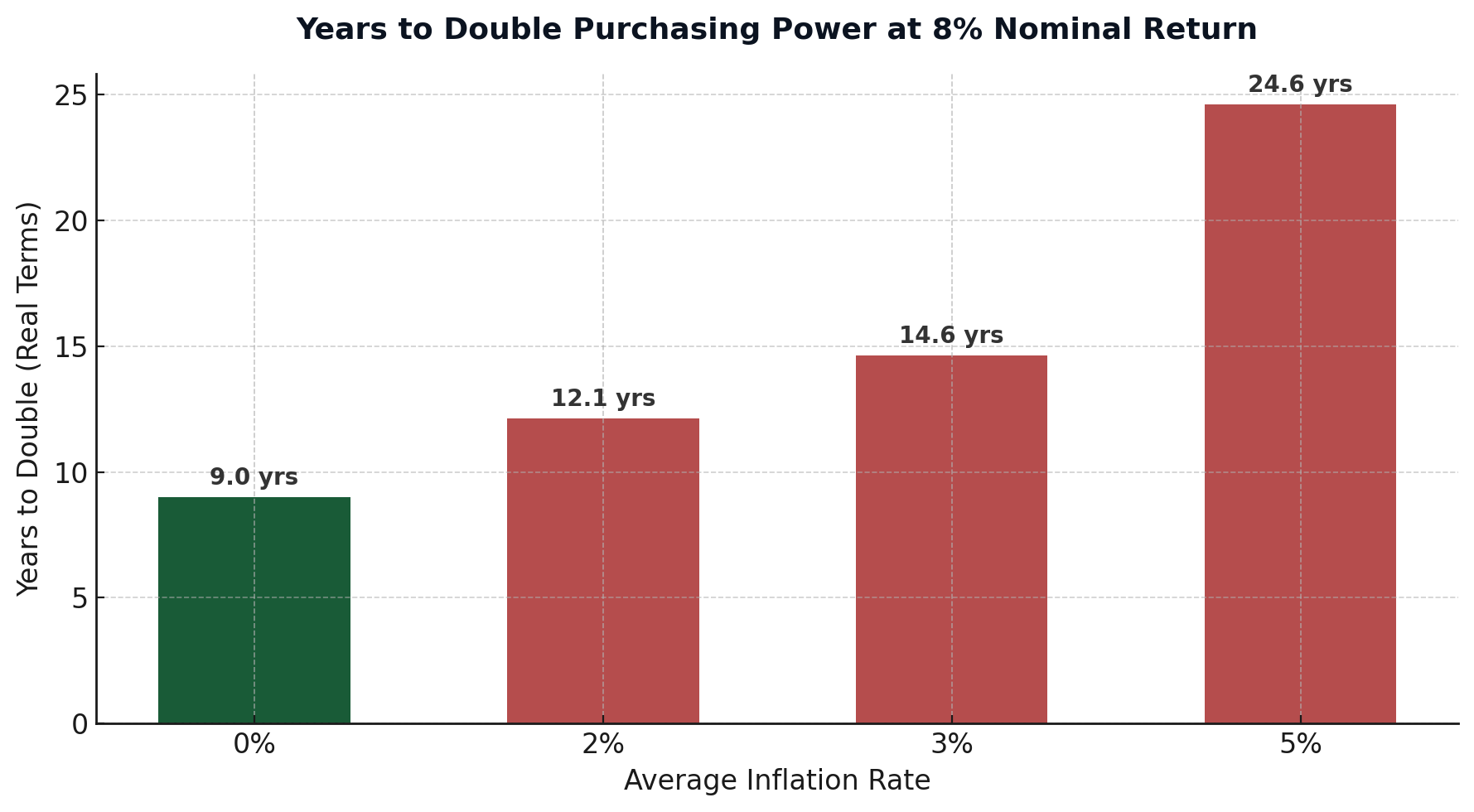

- Inflation compounds in reverse — it steals time by extending how long it takes for investments to double in real terms.

- Real wealth preservation requires inflation-resistant assets such as equities, REITs, and TIPS, which adapt as prices rise.

- Most investors suffer from the money illusion, focusing on nominal returns instead of real purchasing power.

- The most effective inflation strategy is simple: own assets that grow faster than prices, reinvest income, and measure progress in real terms.

The Math of Compounding and Inflation

To understand how inflation undermines compounding, we need to look at the numbers that drive both. Compounding works through the familiar formula:

FV=PV×(1+r)nFV = PV \times (1 + r)^nFV=PV×(1+r)n

where FV is future value, PV is present value, r is the annual rate of return, and n is the number of years invested. This equation assumes that every dollar of growth retains its purchasing power. Inflation changes that.

At first glance, the difference seems small. But compounding magnifies small differences into enormous outcomes.

If your portfolio grows by 8 percent annually while inflation averages 3 percent, your real return is roughly 4.85 percent. That 3 percent drag may sound minor, but across thirty years it can reduce your purchasing power by more than half.

| Scenario | Nominal Return | Inflation | Real Return | Ending Value (on $10,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Compounding | 8% | 0% | 8.0% | $100,626 |

| Inflation Adjusted | 8% | 3% | 4.85% | $41,000 |

This is where most investors misjudge their future wealth. They see a projected portfolio balance that appears to grow exponentially, unaware that inflation has been compounding against them in parallel.

Even modest inflation, compounded over time, erodes purchasing power at a rate that rivals taxes or poor performance. The more years you hold an investment, the more this gap matters.

📊 Pinehold Insight

Inflation compounds in reverse. It quietly multiplies the loss of purchasing power every year, offsetting the very same exponential growth investors depend on to build wealth.

The Silent Tax: Real vs Nominal Wealth

Inflation rarely feels like a threat in the short term. Prices rise slowly, and most investors focus on nominal returns — the number printed on their account statement. But over decades, inflation compounds into a force that rivals taxes, fees, or poor performance. It does not take money out of your account. It simply ensures that the dollars you earn tomorrow buy less than the dollars you have today.

This is the silent tax of investing. It hides behind growth that looks impressive on the surface. A portfolio that doubles in value over twenty years appears successful, yet after adjusting for 3 percent annual inflation, its real purchasing power may have risen by only 50 percent. The investor feels wealthier, but in practical terms, much of that gain is illusion.

History offers clear reminders. In the 1970s, inflation rates above 7 percent erased much of the decade’s nominal stock market growth. Even the 2010s, which many consider a golden era for equities, delivered real returns closer to 6 percent once inflation was factored in. And from 2020 through 2023, a 9 percent inflation spike compressed real returns even in years when portfolios were growing in nominal terms.

The effect compounds invisibly. If an investor targets an 8 percent annual return and inflation averages 3 percent, inflation is claiming nearly 40 percent of the real growth each year. Extend that over thirty years, and the difference between a nominal and inflation-adjusted portfolio becomes almost unrecognizable.

| Period | Average Inflation | Nominal S&P 500 Return | Real Return After Inflation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s | 7.1% | 5.9% | -1.1% |

| 2000s | 2.6% | 4.6% | 2.0% |

| 2010s | 1.8% | 7.6% | 5.8% |

| 2020–2023 | 5.4% | 8.2% | 2.7% |

Inflation is not a single event. It is a slow, consistent erosion that compounds against you. Every year that inflation exceeds expectations, it eats away at prior years of progress. The same exponential power that makes compounding valuable becomes destructive when inflation is applied in reverse.

📊 Pinehold Insight

Inflation is not volatility — it is decay. Market swings come and go, but inflation compounds quietly, shrinking purchasing power even in bull markets that look strong on paper.

Historical Perspective: Inflation’s Long-Term Effect

To see inflation’s full impact on compounding, we have to zoom out across decades. Market performance and inflation rarely move in sync. Some eras allow compounding to thrive. Others quietly destroy its power, even as portfolio balances rise in nominal terms.

From the 1950s through the early 2000s, the U.S. market experienced alternating decades of real expansion and inflationary suppression. The pattern is consistent: when inflation is low and stable, compounding accelerates. When inflation rises, real returns contract — sometimes to zero or even negative territory.

| Decade | Average Inflation | Nominal S&P 500 CAGR | Real CAGR (After Inflation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950s | 2.1% | 19.5% | 17.0% |

| 1960s | 2.5% | 7.8% | 5.2% |

| 1970s | 7.1% | 5.9% | -1.1% |

| 1980s | 5.1% | 17.3% | 12.2% |

| 1990s | 3.0% | 18.1% | 15.1% |

| 2000s | 2.6% | 4.6% | 2.0% |

| 2010s | 1.8% | 7.6% | 5.8% |

| 2020–2023 | 5.4% | 8.2% | 2.7% |

During the 1970s, investors who held stocks throughout the decade saw their portfolios rise in nominal terms, but after inflation, they lost purchasing power. By contrast, the 1990s combined moderate inflation with exceptional productivity and innovation, producing one of the strongest real compounding periods in history.

The 2010s were another decade where low inflation allowed compounding to work freely. A nominal 7.6 percent annualized return converted almost directly into real growth. But the 2020s have already introduced new complexity. Elevated inflation rates near 5 percent have cut effective real returns to half of their nominal level, even during strong market years.

Inflation’s influence becomes especially visible when comparing two investors across decades. The one who compounds during low inflation preserves and multiplies real wealth. The one who compounds during inflationary cycles sees much of that growth consumed by rising prices. Both may appear equally successful in nominal terms, but one retains power while the other loses ground.

📊 Pinehold Insight

The difference between a great investing decade and a disappointing one often has little to do with stock selection or market timing. It depends on whether inflation is helping or hindering compounding beneath the surface.

How Inflation Steals Time From Investors

Inflation does not just shrink returns. It steals time. Every percentage point of inflation extends the years it takes for your portfolio to reach the same purchasing power goal. That hidden delay is one of the least understood consequences of long-term investing.

Imagine two investors aiming to double their purchasing power. One lives in a world of zero inflation and earns 8 percent a year. The other faces 3 percent inflation while earning the same 8 percent nominal return. The first investor doubles their money in about nine years. The second takes nearly fifteen. Nothing about their portfolios changed — the difference is entirely time lost to inflation.

| Target | Annual Return | Inflation | Real Return | Years to Double Real Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal (No Inflation) | 8% | 0% | 8.0% | 9 years |

| Real (3% Inflation) | 8% | 3% | 4.85% | 14.8 years |

This is the invisible cost that never shows up in a performance report. Inflation stretches every milestone further away. Retirement goals take longer to reach, savings targets lose relevance, and compounding needs more time to achieve what once seemed simple.

When inflation is mild, the lost time feels manageable. But over decades, the delay compounds. A long-term investor might lose five to ten years of effective compounding power simply from persistent 2–3 percent inflation. In higher inflation environments, that lost time can stretch beyond an entire market cycle.

The most successful investors are not just those earning high returns — they are the ones minimizing how much time inflation takes away. By focusing on assets that grow faster than prices, reinvesting income, and adjusting expectations in real terms, they preserve both their capital and their timeline.

📊 Pinehold Insight

Inflation robs investors in years, not dollars. Every inflation point delays financial independence and compounds into lost time that no bull market can fully recover.

Compounding After Inflation: The Real Rate That Matters

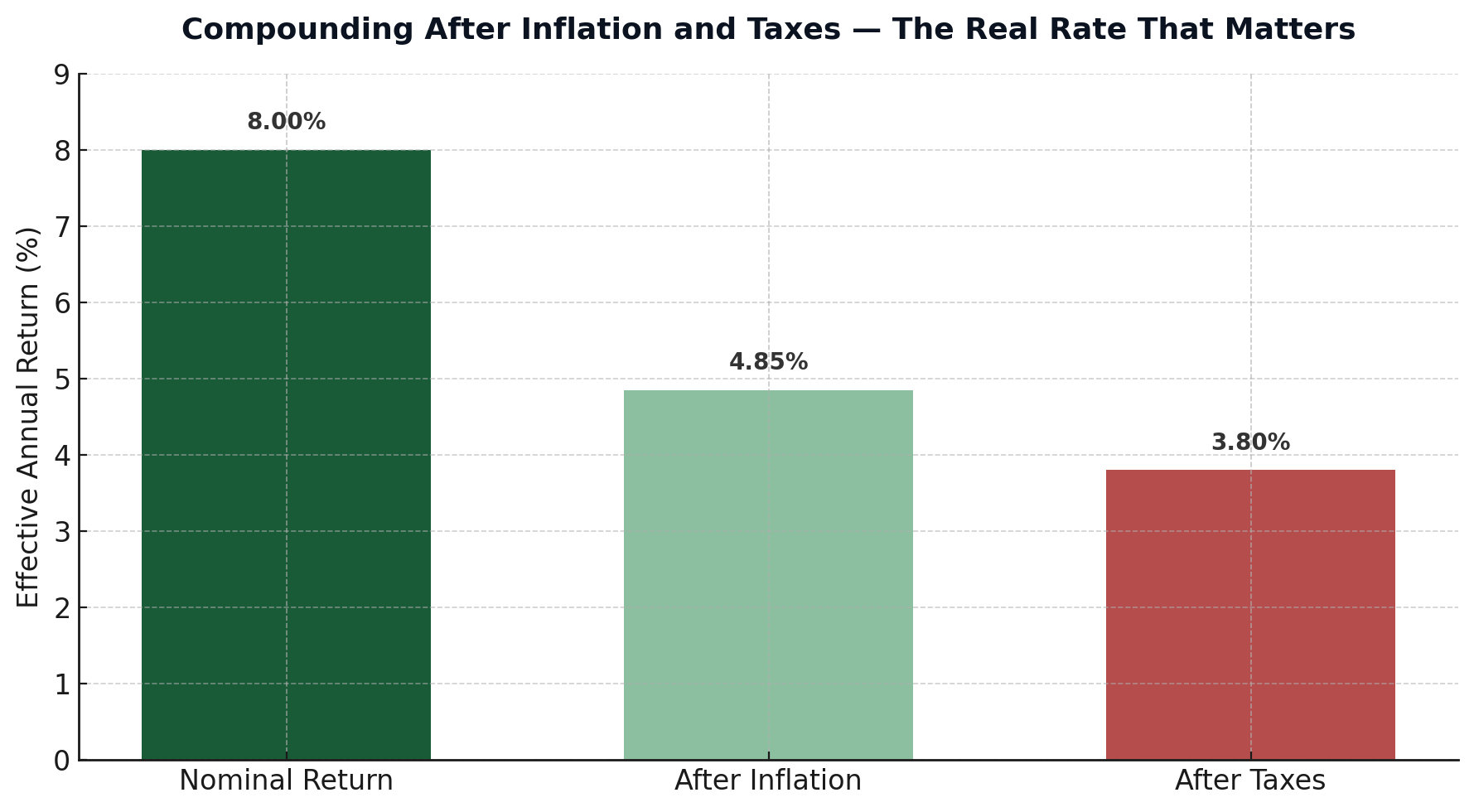

When investors talk about returns, they often stop at the nominal rate — the number their portfolio earned before considering what inflation or taxes took away. But nominal performance alone does not describe how much wealth is being built. What matters is the real return: the growth that remains after inflation has finished compounding against you.

Every investor operates in three layers of return:

- Nominal return — what your account statement shows.

- Real return — adjusted for inflation.

- After-tax real return — what you actually keep.

The difference between them may seem like accounting detail, but over decades it defines the true outcome of compounding.

For example, consider a portfolio that earns 8 percent nominally in a world of 3 percent inflation. The real return is only 4.85 percent. If the investor also pays an average of 1 percent in taxes or fees, the after-tax real return falls to roughly 3.8 percent. That reduction might sound small, but over thirty years, it cuts total real growth almost in half.

| Layer | Return Type | Calculation | Effective Annual Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nominal | Market return | 8.0% |

| 2 | Real | Adjusted for inflation (3%) | 4.85% |

| 3 | After-Tax Real | Inflation + 1% cost | 3.8% |

The gap between what your portfolio earns and what your purchasing power gains is the true measure of financial progress. Inflation and taxes are both silent forces that compound against investors just as reliably as returns compound for them. The longer your horizon, the more critical it becomes to focus on what survives both.

📊 Pinehold Insight

Real wealth is built after inflation and taxes, not before them. The headline return shows what the market gave you. The real return shows what you actually keep.

Inflation-Resistant Compounding

If inflation quietly erodes the value of compounding, the natural question is how to protect it. The answer lies not in chasing nominal performance but in choosing assets that grow faster than prices. Inflation-resistant compounding is about owning things whose income and value adjust with the cost of living instead of losing ground to it.

Historically, three broad categories of assets have outperformed inflation over long periods:

- Equities — Businesses can raise prices, expand margins, and grow dividends in response to inflation. Over the last half-century, equities have delivered real returns near 6 percent annually, even through multiple inflation cycles.

- Real Assets — Investments tied to tangible value, such as real estate, energy infrastructure, and commodities, tend to move in step with price levels. Real estate investment trusts (REITs) in particular have offered both income and partial inflation hedging.

- Inflation-Protected Securities — Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) and inflation-indexed bonds adjust their principal with the Consumer Price Index, directly preserving purchasing power.

No single category is perfect, but together they provide a diversified defense against inflation’s compounding drag. For example, a balanced portfolio of equities, real assets, and TIPS maintained an average real return of roughly 5 percent from 1990 through 2020 — even though inflation averaged 2.5 percent during that period.

| Asset Type | Average Nominal Return | Average Inflation | Real Return (after inflation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equities (S&P 500) | 8.5% | 2.5% | 6.0% |

| REITs | 9.0% | 2.5% | 6.5% |

| Commodities | 6.0% | 2.5% | 3.5% |

| TIPS | 4.5% | 2.5% | 2.0% |

| Bonds (10-yr Treasury) | 5.0% | 2.5% | 2.5% |

The strength of these assets is not that they eliminate inflation but that they allow growth to occur despite it. Dividends rise, rents adjust, and commodity prices reset with the broader economy. The result is a form of compounding that stays connected to real purchasing power rather than detached from it.

📊 Pinehold Insight

Inflation-resistant compounding is not about avoiding inflation. It is about participating in the parts of the economy that benefit from it. Real wealth grows fastest when your income, assets, and time all appreciate with the price of everything else.

The Behavioral Blind Spot

Even when investors understand inflation’s effect on returns, most still fail to act on it. This is not a problem of knowledge but of perception. Inflation is slow, invisible, and easy to ignore. Market volatility grabs attention immediately. Inflation erodes purchasing power silently in the background.

Behavioral finance calls this the money illusion — the tendency to view wealth in nominal terms rather than real ones. A portfolio that grows 10 percent feels successful, even if 6 percent inflation means only 4 percent real growth. Because investors rarely experience the loss directly, they underestimate its long-term impact.

During periods of high inflation, this illusion becomes even stronger. Investors focus on nominal performance and assume the economy is “keeping up.” In reality, rising asset prices often reflect inflation itself, not genuine growth. The psychological comfort of seeing larger numbers hides the erosion of real value beneath them.

Another behavioral pattern amplifies this problem: anchoring to past prices. When inflation pushes the cost of living higher, investors mentally anchor to old expectations of what things “should” cost. As a result, they underestimate future expenses, overstate the adequacy of their portfolios, and delay necessary adjustments to savings or withdrawals.

Inflation’s greatest advantage is its invisibility. It compounds quietly, unchallenged by emotion or awareness. The longer investors ignore it, the more damage it does — not only to portfolios but to decisions about spending, saving, and retirement timing.

The key to overcoming this bias is reframing success in real terms. Investors who evaluate progress by purchasing power rather than balance size develop a truer sense of long-term growth. They plan differently, allocate differently, and stay aligned with their future reality rather than their present comfort.

📊 Pinehold Insight

Markets move fast, but inflation moves quietly. The investors who focus on real wealth instead of visible growth are the ones who keep compounding while others chase illusions.

Lessons for Long-Term Investors

Inflation will always be part of the investing landscape. It cannot be avoided or outsmarted, only accounted for. The investors who outperform over decades are not the ones who find ways to escape inflation, but those who structure their portfolios and behaviors around its presence.

The first lesson is to measure progress in real terms. A 10 percent nominal return may sound impressive, but its real significance depends on the inflation rate beneath it. Tracking inflation-adjusted returns reframes success in purchasing power — the only metric that ultimately matters.

Second, own productive assets that rise with prices. Stocks, real estate, and businesses grow revenues as costs increase. Bonds, fixed annuities, or unadjusted cash holdings lose ground when inflation persists. A portfolio tilted toward assets that adapt to inflation preserves the true benefit of compounding.

Third, reinvest income and dividends. Inflation raises prices, but it also increases nominal cash flows. By reinvesting, investors capture those higher cash amounts and convert them into additional compounding power rather than letting inflation erode them.

Fourth, control costs and taxes. Inflation compounds in reverse, but so do fees. Every fraction of a percent lost to expense ratios or unnecessary turnover becomes a permanent drag on real returns. Minimizing friction keeps more compounding power intact.

Finally, stay patient during inflationary cycles. Short-term reactions — shifting to cash, reducing equity exposure, or chasing inflation hedges — often produce lower long-term returns than simply staying invested in adaptive assets. Compounding rewards consistency far more than activity.

| Strategy | Effect on Inflation-Adjusted Wealth |

|---|---|

| Measure real returns | Reveals true growth vs illusion |

| Own real assets | Offsets inflation through pricing power |

| Reinvest income | Converts inflation into new growth |

| Reduce costs | Preserves compounding efficiency |

| Stay patient | Lets time and adaptation do the work |

Over the long run, the investors who internalize these lessons view inflation not as an enemy, but as a constant variable in the equation of compounding. They know that the power of time only matters when measured in real terms, and that every financial plan is ultimately a race between growth and erosion.

📊 Pinehold Insight

Inflation is not the end of compounding — it is the test of it. The investors who adapt their strategy to inflation’s pace are the ones whose wealth endures across decades.

Compounding’s Real Power

Compounding and inflation are two sides of the same long-term equation. Both build over time, both accelerate quietly, and both shape the real outcome of an investment. Understanding how they interact is essential for setting realistic expectations about future wealth.

Compounding increases portfolio value, but inflation determines what that value is actually worth. Investors who focus only on nominal growth often overestimate their long-term results, while those who evaluate performance in real terms gain a clearer view of their progress.

An 8 percent nominal return in a 3 percent inflation environment is not eight percent wealth creation. It is roughly five percent real growth. Over three decades, that difference compounds into a wide gap between perceived and actual purchasing power.

The true value of compounding lies in maintaining growth that exceeds inflation consistently. This requires discipline, diversification, and a long-term focus on assets that adapt as prices rise. Inflation will always exist, but its effect can be managed through steady real growth over time.